What is grooming and mite biting?

Grooming is a behavioural resistance mechanism where bees remove mites from themselves (autogrooming) or nestmates (allogrooming). Bees have a unique grooming invitation dance that communicates to nestmates that they need assistance. Bees performing this dance are more likely to be groomed.

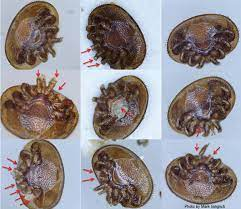

Damage to mites caused by grooming (red arrows). Photo: Mark Gringrich

Bees continue to bite and injure the mites’ legs and idiosoma (body) after removal from the bee. These injuries reduce mite fitness and reproductive capacity. For instance, injuries to the forelegs of the female Varroa mite interfere with the pit sensory organ used in chemosensing and attachment. These are used by mites to find suitable hosts, such as nurse workers, which are more likely to bring them into contact with brood. Mites with impaired pit sensory organs couldn’t maintain preference for nurse bees and their reproduction in brood cells was significantly impaired. Mite biting bees may target mite forelegs.

Grooming is measured by placing sticky mats on the bottom board for two days and counting the number of mites that fall. As there is natural mite fall, due to natural attrition of mites, mite biting is measured by calculating the proportion of mites on the sticky board that have been damaged by examining them under a microscope for damage to legs or body. Mite injuries can result from factors other than bees.

Breeding efforts

Purdue University and Ohio State University, in collaboration with regional queen bee breeding associations have pioneered breeding for grooming and biting behaviour. This is partially done through identifying and breeding “survivor stock” that survives with no or little Varroa treatment and selecting for high grooming and biting.

Through these efforts physiological changes have occurred; mite biter bees have shorter mandibles compared to commercial stocks.

Where bees are selected for low mite population growth – a cornerstone to resistance found in Varroa Sensitive Hygiene programs – they also tend to be better groomers and biters.

Studies have found that grooming is highly heritable in some populations but not in others. In populations where it is high it would be possible to select for this trait, while in populations where it is very low it would be impossible.

More information

- Video – New breed of Ohio honeybees fights harmful parasites https://www.foxbusiness.com/video/6330320222112

Acknowledgements:

- Resilient beekeeping in the face of Varroa. AgriFutures Australia. Holmes, Gerdts, Grassl, Mikeyev, Roberts, Remnant, Chapman

- Varroa – breeding for resistance. AgriFutures Australia and AHBIC. Holmes, Gerdts, Grassl, Mikeyev, Roberts, Remnant, Chapman

- Guichard et al (2020) Advances and perspectives in selecting resistance traits against the parasitic mite Varroa destructor in honey bees. Genetics Selection Evolution 52: 71

- Hunt et al (2016). Breeding mite-biting bees to control Varroa. Bee Culture 8: 41-47

- Land & Seeley (2004) The grooming invitation dance of the honey bee. Ethology 110: 1-10.

- Morfin et al (2023) Breeding honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) for low and high Varroa destructor population growth: Gene expression of bees performing grooming behavior. Frontiers in Insect Science 3: 951447

- Mukogawa (2022) The role of social immunity in feral honey bees (Apis mellifera) in response to the parasitic mite (Varroa destructor). Doctoral dissertation, UC San Diego

- Nganso et al (2020) How crucial is the functional pit organ for the Varroa mite? Insects 11:395

- Smith et al (2021) Morphological changes in the mandibles accompany the defensive behavior of Indiana mite biting honey bees against Varroa destructor. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 9: 243

- This article was peer-reviewed by Michael Holmes and Nadine Chapman.