Barley scald is caused by the fungus Rhynchosporium commune (formerly known as R. secalis) and is common all barley growing regions. Its severity varies significantly within a given crop, between crops and seasons, depending on seasonal conditions. It is most prevalent in high rainfall seasons, particularly following an early and wet season break. Grain yield losses due to scald are generally 10-20 per cent in susceptible varieties, while individual losses can be as high as 40 per cent.

What to Look For

The disease causes lesions of the leaf blades and sheaths. At first, scald appears as water-soaked, grey green lesions, which change to a straw colour with a brown margin that are ovate to irregular in shape.

Scald of barley. Early water-soaked, grey-green symptoms compared to later straw colour lesions with a distinctive brown margin.

Scald of barley. Early water-soaked, grey-green symptoms compared to later straw colour lesions with a distinctive brown margin.

In severe infections, the disease can cause complete defoliation by coalescing of the lesions.

Disease Cycle

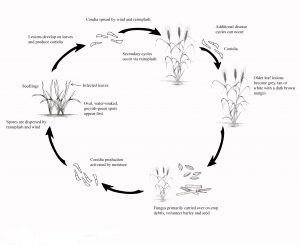

Rhynchosporium commune (Scald) survives over summer and autumn on stubble of infected plants. Spores are dispersed from the stubble during Autumn by rain splash into the new season’s crop, where they start the primary infection. Scald is usually first observed in isolated patches of a crop when plants are tillering or at early stem elongation. Further spread can be rapid during warmer conditions (15-20ºC) and is caused by splash dispersal of spores. By the end of the growing season scald can be found throughout the crop with distinct hotspots. The disease is most severe in seasons of above aver- age rainfall, particularly during the winter and spring.

Scald can also be seed-borne, can infect barley grass and survive on volunteers. These sources are less important than infected stubble but can be an inoculum source, especially during seasons with favourable climatic conditions.

Management

Cultural Practices

Carry-over of scald inoculum can be reduced by using crop rotations that avoid consecutive barley crops and ideally a two year or more break between barley crops. This allows infected crop residue to breakdown. Grazing, burning and cultivation of stubble, volunteers and barley grass, can reduce inoculum loads but do not eliminate the disease as scald will survive on small amounts of remaining residue. Scald is also more severe in early sown crops, so avoid early sowing of susceptible varieties, especially in high rainfall areas to reduce the risk of loss caused by scald.

Resistant Varieties

Cultivation of resistant varieties gives the best control of scald, with the risk of grain yield and quality loss being greatly reduced by avoiding growing susceptible and very susceptible rated varieties. Unfortunately, R. commune is highly variable pathogenically and able to overcome resistances rapidly, mean- ing that many varieties are susceptible to current strains. It is important to check a current Victorian Cereal Disease Guide or the NVT website for the resistance status of varieties.

Fungicides

There are a range of fungicides available that will provide suppression of scald. Fertiliser and seed applied fungicides provide effective suppression during the seedling stages of crop development, while foliar fungicides are most effective when applied during the beginning of stem elongation (GS31) to flag leaf emergence (GS39) stages. Two applications of fungicide are generally required to minimise grain yield and quality loss where disease pressure is sustained during the season.

Application that coincide with the early stages of scald development are more effective than later applications as scald can rapidly cause damage when conditions are favourable. Crop monitoring is very important during seasons of risk of scald development.

Please note: This book is also available on AppleBooks