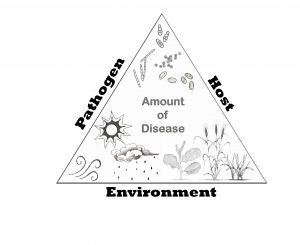

The major factors affecting disease severity can be linked together in the Disease Triangle.

Each side of the triangle represents one of three components: environment, host and pathogen. Each of these three components are required for disease to occur. For example, if you remove the susceptible host and grow a non-host species, you will get no disease.

The environment has a major influence on the infection process and often determines the incidence and severity of a disease. If conditions are too dry or too cold the pathogen may not be able to successfully attack the plant. For example, for stripe rust infection to occur there needs to be between 5-6 hours of leaf wetness (or high humidity) with a temperature range of 9-18°C. These requirements are different for other pathogens, but moisture is a relatively consistent requirement for initial infection to occur.

Conditions needed for development of rusts in wheat

| Crop | Disease | Pathogen | Temperature Range °C | Optimal Temperature °C | Leaf Wetness* (Hours) | Latent Period# (Days) | Spore Dispersal | Primary Inoculum Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | Leaf rust | Puccinia triticina | 10-35 | 15-25 | 3 | 7-10 | Wind | Volunteer wheat |

| Stripe rust | Puccinia striiformis | 0-23 | 10-15 | 3 | 20-86 | Wind | Volunteer wheat | |

| Stem rust | Puccinia graminis | 15-40 | 20-30 | 6-12 | 14 | Wind | Volunteer wheat |

(#) The latent period is the amount of time after infection before symptoms are present. It generally decreases as temperature increases within the optimal range.

While there are generally more disease problems in wet years, different seasonal conditions will suit different diseases and change the impact they will have on crop yields. For example, wet springs will favour the cereal root disease Takeall, while dry springs favour Crown rot expression. The term ‘expression’ is important as the crown rot fungus may infect plants every year, however, the expression of the whitehead disease symptom is what results in yield loss. This is why the environment is a critical component of disease development.

The chain of events that occurs during disease development is called the disease cycle. The incidence and severity of the majority of plant diseases vary on a distinct cyclic basis. Each cycle includes two alternating phases; the parasitic phase and the survival or over-summering phase.

Survival over summer (or from one crop to the next) is dependent on environmental conditions and the environmental requirements of the pathogen. Rhizoctonia and Take-all survive well during dry summers when there is little break down of plant residues or competition from other organisms in the soil. Rusts on the other hand survive only on living host plants and their survival is favoured by wet summers which support growth of volunteers (i.e. green bridge).

For a disease to establish the pathogen must first come into contact with the host plant. This disease inoculum is generated by previous infections and liberated into the environment; it may come from the same location or have travelled over great distances. Inoculum may be primary (resulting from infections in the previous season), or secondary (arising from infections in the same season).

Wind is the most important way in which fungal spores (e.g. rust spores) are disseminated over long distances. Rain splash is important for some fungal pathogens (e.g. Septoria) to spread,

especially over short distances. Water also plays an important role for fungus like organisms pythium and phytophthora (oomycetes) allowing their free swimming spores move rapidly from host to host.

For other diseases (e.g. Rhizoctonia, Take-all, Crown rot) the inoculum comes from infected plant debris remaining in the soil. Over the past few centuries humans have become one of the most effective ways in which crop diseases are spread. On a local scale this includes machinery, vehicles, and clothing but are not limited to these. This can be taken to a global scale where airplanes, ships and other transport

Disease Epidemics

When referring to disease epidemics the disease triangle becomes a complex interaction between the pathogen, host plant, environment, and time. By incorporating time, disease spread and severity can be demonstrated. A change in environment over time can reduce the severity of the epidemic or increase the severity depending on the conditions. For example, an initial stripe rust infection may not result in an epidemic depending on the conditions following the infection. However, if conditions are conducive, no management is undertaken, and the host is susceptible then these are the conditions for an epidemic.

The distribution and genetic diversity of host populations are of great importance in determining the degree and rate of epidemic development.

As an example, if a whole district is planted to a wheat cultivar susceptible to Stripe rust (e.g. cv. Mace in eastern Australia) and Stripe rust become established there will be a large pool of spores to spread, thus increasing the risk of an epidemic.

The risk of a disease outbreak also increases if there is an over reliance on one resistance gene for disease control. This puts a very high selection pressure on the pathogen and mutations that have overcome that resistance gene can rapidly increase in the population.

Diagnostics Checklist

Plant diseases can be difficult to diagnose, but good diagnosis usually starts with gathering background information as well as the symptoms observed. For example, there may be some discolouration on wheat roots, but paddock history shows that root lesion nematode susceptible crops were grown. Also, knowing the susceptibility of the variety to important diseases, herbicide history of the paddock can all help with diagnosis.

For diagnosis, it is helpful to know:

- sorts of disease expected at the particular time of year or under the prevalent weather

- common diseases of the host in question

- sorts of troubles peculiar to the area.

The following is an outline of some of the causes and characteristics of the more common diseases and disease-like symptoms seen in crops and things to consider during your diagnosis.

Symptoms of Common Diseases

When diagnosing symptoms, you’ll need to investigate the:

- internal, as well as, the external parts of the plant; attempt to determine what part of plant was affected first

- history of symptoms

- leaves and stem(s) of affected plants

- flowers

- roots (dig up suspect plants, wash soil from roots and examine carefully – preferably in a tray of water).

Distribution of Affected Plants

The distribution of the affected plants within a paddock can often help point to whether symptoms are caused by a disease or some other factor. Take time to get a thorough overview of symptoms in the crop. Make a sketch or take a photograph.

Affected plants occurring in rows or lines could indicate:

- malfunction of equipment such as sowing depth or problems with fertiliser or herbicide application

- herbicide spray overlap

- infectious disease spread by contact and consistent with cultural operations

- a pathogen like cereal cyst nematode that can be dragged along the rows during cultivation.

Random individual affected plants may be caused by:

- seed-borne disease

- spores blown in from a great distance

- an insect that spreads the pathogen.

Affected plants that are more concentrated on the edges of the paddock, may be caused by:

- insect vectored disease

- spores or cysts blown in from adjacent paddocks

- pesticide drift from adjacent paddocks.

Affected plants occurring in patches could indicate:

- soil-borne disease such as cereal cyst nematode or Rhizoctonia root rot

- soil type

- insects such as aphids, or virus spread by aphids.

Uniformly affected plants across the paddock, more likely to be caused by:

- herbicide damage

- nutrient deficiency or toxicity

- stubble-borne diseases.

While there are a number of diseases that affect each crop, most have key characteristics that can be used to help identify them in the field. The symptoms associated with common field crop disease in Victoria are discussed in the following chapters. These include diagnostic features, potential yield loss and key management strategies.

Please note: This book is also available on AppleBooks